Public theatre – refuge under pressure

The year 2015 looks set to be the year of celebrating the Polish theatre. Exactly on 19th November 2015, we shall be celebrating the 250th anniversary of the first performance by a company established upon the initiative of king Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski, being the germ of the first professional Polish public theatre. For many years, the opening night of the comedy Intruders [Natręci] by Józef Bielawski on a November evening of 1765 has been considered the beginning of an institution so vital for Polish life, the National Theatre, and at the same time the beginning of the history of institutionalised public theatre. As a consequence, in 2015 we celebrate two anniversaries: 250 years of the National Theatre in Warsaw and two hundred and fifty years of public theatre in Poland.

While the former seems to be easy to understand (which does not mean that it is not problematic), the notion of "public theatre" requires clarification and explanation. From the economic and organizational point of view, public theatre differs from other types of theatres (above all private ones) through the fact that it is funded from public (national, local) means because of its importance and the value it brings to social and individual life, as well as to heritage and national culture. Such a definition is a kind of a “hard core" of the public theatre, allowing us to quickly delineate its boundaries and define its goals. This theatre - quite simply - does not work for profit, but for the public benefit. Its goal is not to achieve the greatest financial gain but to support and develop intangible assets, often unjustly neglected today, and in many cases determining the survival and success of community and its constituent individuals.

This obviously does not mean that public theatre can operate outside of the rules of economics and rational financial management. It means, however, that in its case not the economic conditions and objectives are the most important, of which - especially now, in the times of the tyranny of economics – one needs to be almost constantly reminded. To quote a great actor and director Juliusz Osterwa: public theatre is not a company, but an undertaking.

Several meaningful consequences and problems of fundamental importance for the history and the presence of theatre stem from that.

The basic question is: how to define the “intangible assets”? Who has the power and authority to decide about non-economic dimensions of public theatre?

The answer is by no means simple, and the history and contemporary events show how different the answers can be. And here comes the second fundamental meaning of the word “public”, referring to the idea of public space and public debate meaning the space and the process of free exchange of views, discussions aimed not (as is happening alarmingly often today) at destruction and oppression of the enemy, but at developing solutions that are acceptable to the largest possible group of fellow citizens. In this context, public theatre is a part of public life, a civil institution, a place and a tool of debate on topics that the community considers to be most important for itself.

This social dialogue takes place in the theatre in a different way than in other places where it is conducted. It is not an exchange of views, a dynamic dispute of rights. It is based on a presentation by artists, with specific skills as well as a kind of human and social sensitivity, of comprehensive and complex diagnoses related to the community and the individuals who create it. The diagnoses can be (and often are) provocative in nature, they can be critical attacks, or simply mockery and irony, but just then they have a chance to cause a reaction and reflection.

Interiors of the national theatre in 1790 (oil on canvass, unknown author).

Interiors of the national theatre in 1790 (oil on canvass, unknown author).

The strength of the theatre has always been made up of two of its elementary and closely connected features: the ability to present complex reality in a synthetic manner and the process of direct interaction between all the people involved in the theatre event – the performance.

It is not easy to translate these mechanisms into words, but everyone who goes to the theatre knows how very different the images of life displayed on the screen (all the same: in the cinema, on TV or a computer screen) are from those that are created by real actors, who are present here and now with us. Despite relatively small range of influence, the power of theatre exchange of thoughts and feelings is enormous, also because the theatre - as a living and multidimensional art - gives to its creators and spectators the opportunity to experience the incredible complexity of the world. The very fact that at the same time an actress and her character are standing in front of us sensitizes us to something we so often forget nowadays: that reality (especially human reality) is multiform, multifaceted, far from unifying patterns and stereotypes. The theatre teaches us to recognize the multiplicity, sensitizes us to the dissimilarity, shows its value, and urges us to reflect upon our own beliefs and attitudes.

Particularly public theatre fulfils these functions in a special way. This does not mean that private theatre does not fulfil them. Since they are the power of theatre in general, it seems obvious that their fulfilment does not depend on who pays for the theatre. But it is easy to notice that in a situation where the institution is dependent on financial input, it is much more difficult for it to oppose to the beliefs that dominate in the society, it is much more difficult to shake and critically challenge the stereotypes functioning in the community since time immemorial. A much greater threat lies also in limiting oneself purely to entertainment, that is - according to the principle of engineer Mamoń - still playing the same favourite, well-known songs. Entertainment theatres are obviously needed and no reasonable person will aim to close them down or recognize as harmful, but their function and principles of operation are totally different than those of the public theatre, which, since it often goes precisely against the audience, should be under special protection.

Everything that I said above leads to the formulation of several important conditions for the existence and functioning of public theatre in accordance with its social – let us not be afraid of the word - mission.

Revenge [Zemsta], dir. Jerzy Krasowski, photo by Grażyna Wyszomirska

Revenge [Zemsta], dir. Jerzy Krasowski, photo by Grażyna Wyszomirska

The first one is: public theatre should be accessible for everyone, and open towards variety of opinions and views, even of those who do not accept it (then, they can or even should critically reflect upon them, start a discussion, initiate a debate about them). It is a condition sine qua non for the public theatre not to fall into harmful one-sidedness. Moreover, it means the necessity to actively look for opportunities to meet and confront different groups of spectators, including going on tours, undertaking educational activity and looking for ways to make theatre accessible to people with limited economic means. Limitation solely to the circles of experts and theatregoers is one of the greatest dangers that threaten public theatre.

Another problem involves the relationship with authorities, which have at their disposal public funds earmarked for the functioning of theatre. In the past, as well as today, it has sometimes been used as a tool of political and ideological control. The boundaries between the reasonable and necessary control of prudence and economy in the use of taxpayers' money on the one hand, and the exercise of ideological and political supervision, or even censorship and restrictions on freedom of speech and artistic expression on the other, are very fluid and difficult to squeeze into a rigid frame of legal rules. To avoid crossing them, wisdom and maturity of both the government and the people of theatre are necessary. Both parties should be aware that they are not the owners of this amazing tool, but its disposers, obliged to use it in the best possible way.

Public theatre understood and practiced in such a way has a chance to become a space of creative and intellectual freedom, a tool of critical thinking. The latter seems to be very important, and let me emphasize once again that the public theatre is a space of experience and reflection, whose essence is confrontation with the ways of thinking adopted and implemented by the spectators in life.

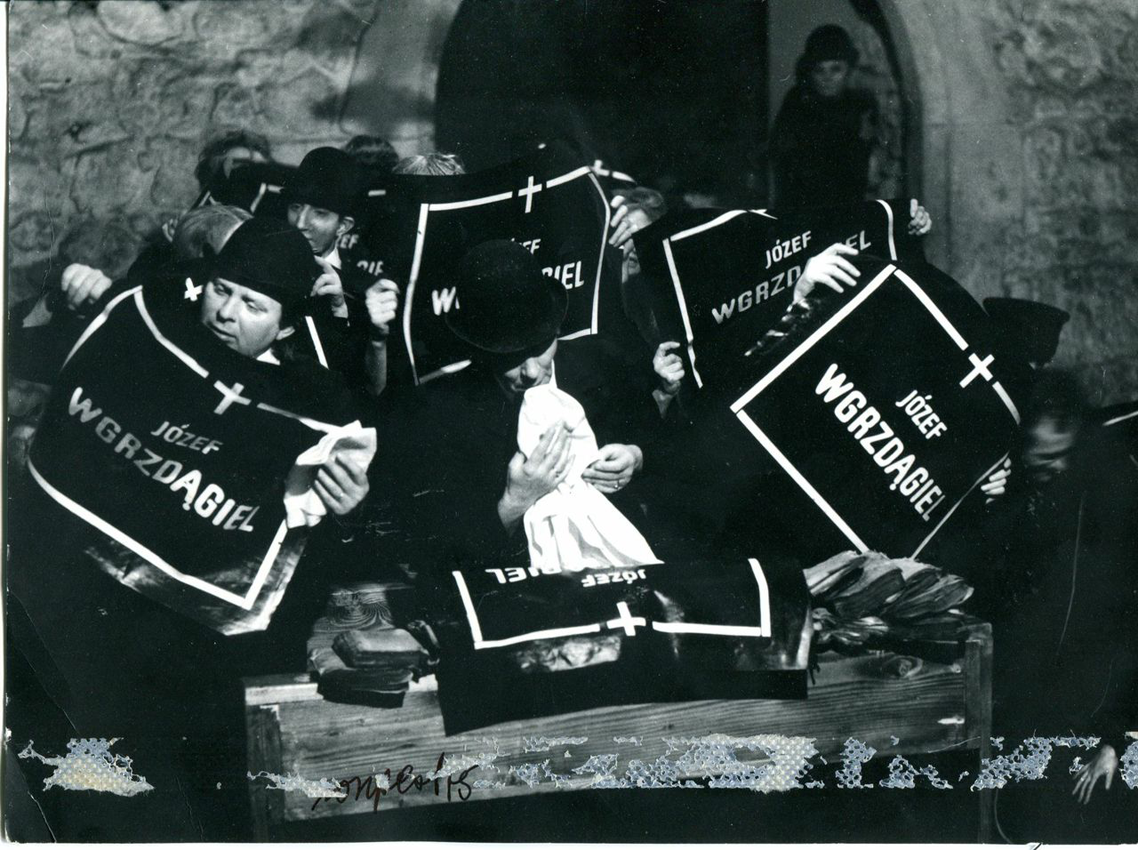

Apocalipsis cum figuris, dir. Jerzy Grotowski, photo by Piotr Barącz

Apocalipsis cum figuris, dir. Jerzy Grotowski, photo by Piotr Barącz

There is no doubt that the theatre does not have the same reach and impact as the cinema, television or the Internet. But precisely because of that it retains its importance as a place of confrontation and reflection. People protesting against theatre performances that are contrary to their views, tastes and perceptions often use arguments transferred from other media, much more mass in nature. Meanwhile, it is that certain elitism and intimacy of the theatre which makes it retain its unique position in the world of the means of mass communication destruction. Acting on a relatively small scale, it has the opportunity not to develop horizontally – increasing its range, but to go into deep – problematizing and posing new questions. In the nineteenth, and possibly even in the twentieth century, theatre was frequently the “temple” of collective ecstasy and quasi-ritual experiences. In the twenty-first century, it seems to run away from it, recognizing its place on the other pole of collective ceremonies – as a tool of scepticism, criticism and often mocking irony, a form of protection against the dangers of mindless succumbing to collective emotions.

An important element of public theatre understood in such a manner is undertaking dialogue with the past. This is yet another flashpoint which, especially in Poland, when faced with the still lasting impact of tradition, causes many disputes and conflicts largely centred around the concept of “classics”. Again, the case is very complicated and complex. On the one hand, it is reasonably expected that in particular the public theatre should maintain ties with the past, also in terms of work to preserve this part of the intangible heritage which belongs to the realm of theatre. A great example of it are the comedies of Aleksander Fredro, associated with the acting tradition preserved for many years and passed down through generations from hand to hand. This tradition – the manner of pronouncing the text, interpretive and executive tradition – is a value in itself, just like the old wedding customs, folk songs and dances, or carollers’ performances. It cannot be stored in museums and archives, since it only exists alive, incarnated by actresses and actors. Its social context disappeared, like the social context of the wedding ritual of governor’s recitation or the Beilager did, but that does not mean that we are to renounce it, thus depleting our native tradition. On the other hand, public theatre, following its vocation, felt particularly strongly in the contemporary context, is not willing to undertake uniquely “archaeological” work on historical conventions and ancient texts. Usually, it refers critically to the past, exposing the hidden presence and power that anachronistic schemes and myths still exercise over today's Poles, or exposing its dark side. It is impossible to impose a certain attitude towards the past on theatre artists. At most one can encourage them and provide them with the opportunity to pay more attention to the achievements of their predecessors, treat them as partners and allies, older brothers, whom, while still being critical, one must also respect. And this particular attitude was actually the origin of the competition for Staging Early Works of Polish Literature “Classics Live”, which was organized by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage to commemorate the 250th anniversary. The winners will be chosen in November 2015, and already today I am looking forward to its results.

When writing about all the tasks and functions of the public theatre, it is impossible not to notice that their implementation requires perfecting of technique and artistic skills, and often seeking new ways of doing things and new means of expression. To a certain extent, public theatre was and is a tool for working out innovative methods of work and training, staging and acting proposals which surprise with their originality, unusual readings and provocative interpretations.

It is impossible at this point not to recall that the two most “laboratory” Polish companies of the twentieth century: the Laboratory Theatre of Jerzy Grotowski and Cricot 2 of Tadeusz Kantor were in terms of their organizational form public theatres, and although they were often treated as exotic “experiments”, today it is particularly visible that The Dead Class [Umarła klasa] or Apocalypsis cum figuris are examples of extremely intense experiences affecting the public sphere.

The Dead Class [Umarła klasa], dir. Tadeusz Kantor, photo by Wojciech Szperl

The Dead Class [Umarła klasa], dir. Tadeusz Kantor, photo by Wojciech Szperl

Also nowadays, performances by Krystian Lupa and Krzysztof Warlikowski, original and appreciated for their artistic innovativeness, are spaces of very intense debate on issues of key importance for social life.

Obviously the above mentioned functions are not all that the public theatre fulfils. It is a meeting space, a kind of social celebration standing out against the background everyday life. It is also a sign of prestige, a symptom of cultural power of the environment – the city, the region – where it exists and works. It is finally also a place of rest, a break from the usual course of action. Today it is also – and this aspect should be particularly emphasized – a cultural institution whose activities go beyond the preparation and presentation of performances. Theatres organize discussions, workshops, concerts and presentation of other art works, they serve as galleries, publish books and magazines, carry out educational projects ... They are thriving cultural centres, often with a supra-regional reach, helping to change the image and attractiveness of places in which they operate.

And also in that way they emphasize and play their role of a public institution, which contributes to the development of the public sphere and affects its shape in a way that is not necessarily impressive and spectacular, but rather more subtle and indirect. Thus, declarations and attempts to place this sphere under strict political control, limiting its freedom, often coupled with misleading calls to meet the expectations of the “average spectator”, awake all the more concerns. It is an open secret that many theatres in Poland are at risk of alienation, shutting themselves out only in the company of their admirers, that when it comes to the issue of establishing a genuine dialogue with the audience many theatres still have much to do. But these efforts are underway, and it is not true that Polish theatres do not listen to the ”average spectator”. This does not mean, however, that they have to act like another public institution, destroyed by money and politics – television. Now that viewing rates and related hypocritical sweetness rule everywhere and everything, perhaps we should leave to ourselves this relatively small refuge – the theatre – to have a place where we could hear a few awkward and angular words from time to time, laugh at ourselves and see that life can also be elsewhere.

Dariusz Kosiński